Beating the odds

I was alerted to Kobe Bryant’s passing by a text from my best friend. Waking up from a nap, I looked at my phone to see he had asked if I was okay, saying something about “that Kobe death.” Still coming to, I went to Twitter to see what he was talking about.

It made sense to learn Kobe had been in a helicopter crash. I had known for years Kobe commuted in a chopper, but having been asleep, I figured I wasn’t caught up. I scrolled, looking for a headline. “Kobe transported to hospital following helicopter accident, condition unknown,” I thought it would read.

All my life I’ve known Kobe to beat odds; not defy them or overcome them, but beat them. Defiance can be circumstantial, passive even. One can overcome by mere chance. Countless times, I had seen Kobe square up to the odds, state his intent and beat them in certain terms. I wasn’t in denial or incredulous. I had just seen this movie before.

Kobe had been in an accident. He was injured, in critical condition, maimed even; he wasn’t dead. Of course not.

Tears and milestones

After dispatching my beloved Sacramento Kings in the first round of the 2000 NBA playoffs, the Lakers met the Portland Trailblazers in the Western Conference Finals. I was upset at what had happened, not only in the previous weeks, but all season. The Lakers had also beaten my Kings twice in pretty upsetting fashion in regular season matchups. I knew they would beat whatever team won the East. Portland was the last hope.

The deciding game seven coincided with a birthday party at a family friend’s place, in a suburb just south of Sacramento. While other kids in attendance played outside, I watched with pleasure as Kobe and the Lakers fell down by double digits, paying more attention to the game than the cake and ice cream. I was going to school the next day to rub this in the faces of all the Laker fans who laughed at me after they eliminated the Kings. I grew anxious as Portland fell apart. The Lakers eventually took the lead in the fourth quarter and with less than a minute left to go, Kobe lobbed the ball to Shaquille O’ Neil for a dunk that would put the game out of reach. I bowed my head, covered my face with my hands, and let out a single tear. At age 10, this was the first time I remember crying over sports.

By 2002 my Kings had become the best team in basketball. The team finished the regular season with the NBA’s best record and met the Lakers in the Western Conference Finals. As in 2000, I knew the best from the West would go on to win it all. This time, my team was going to do the honors.

I vividly recall sitting on my aunt and uncle’s couch on a Sunday afternoon, after playing some ball myself. I watched my Kings build a 17-point lead on the Lakers’ home court.

“They’re (the Kings) better than them (the Lakers),” my dad said matter-of-factly.

He was right. The Kings had been the better team by most metrics for months, and here they were on the cusp of going up three games to one in the best–of–seven series, with two of three possible games to be played in front of a Sacramento crowd that had created basketball’s best home court advantage. The Lakers came back. They won that game and the series, then their third straight championship. Of course they did.

On New Year’s Day in 2010, I watched the Kings play a regular season game against the Lakers. A Sacramento player (whose identity escapes me) missed a free throw that would have given the Kings a comfortable lead with 4.1 seconds to go. My mother, who I was watching the game with, said something to the effect of, “Well, they’re still up.”

“Won’t matter,” I responded. “Kobe’s going to get the ball, he’s going to score, and they’re (the Kings) going to lose.”

And he did. Of course he did. It was one of seven game-winning shots he made that season, an NBA record.

The following year, the family that owned the Sacramento Kings had begun the process of relocating the team to Southern California. They wound up staying, but in the spring of 2011, this seemed unlikely. The last game of the season, which could have been their last ever game in Sacramento, was against Kobe Bryant and the two-time defending champion Los Angeles Lakers. The Kings fell behind big. The game looked like it would be anti-climactic, but this time it was my team that made the comeback. With less than 10 seconds to go, the Kings were up by three, at the time I believed this would be the last time I saw my favorite team play with my hometown embroidered on their uniforms. But for one night, they were gonna reverse historic roles. Kobe caught the ball on the right wing, he took one dribble and he rose up for a three-pointer that would tie the game.

Of course he did.

After the overtime, he’d finished with 36 points that night to lead the Lakers to victory over my team one last time (or so I thought at the moment). Of course he did. I hugged my dad, thanked him for introducing me to my favorite sport and team, and let out several tears. It was the second time I remember crying over sports.

It wasn’t until years later that I truly appreciated Kobe’s brilliance. Having rooted against him for so many years, I always made a point to identify his flaws: too many shots, regardless of how many he made; abrasive and volatile with his teammates; self-centered, I would say.

But Kobe always sought out challenges, like going to the NBA immediately after high school, welcoming comparisons to Micheal Jordan, widely believed to be the greatest basketball player of all time, and seeking to win championships without his hall-of-fame teammate (O’Neil) because he thought himself a capable leader.

Kobe was always convinced of his capacity, his value and his purpose.

So convinced, in fact, that he once took just three shots in the second half of a 2006 playoff loss because he had been accused of hogging the ball. His message in doing so: “If I’m such a problem, try winning without me.”

“Petulant,” I said to a high school teammate who adored Kobe.

In 2016, on the day of Kobe’s last NBA game, I had a job interview. It was the culmination of four years of work since I’d gotten serious about becoming a journalist. I was a candidate for a position with a three-letter network’s Sacramento affiliate, the sort of job people can’t wait to mention after being asked what they do at a party. I wasn’t nervous. I was distracted for most of the day, anxious to see Kobe’s last game.

To finish his final season, one during which he averaged 17 points per game on a Lakers squad that had won just 16 of 81 games to that point, Kobe scored 60 to lead the Lakers to a win after trailing the Utah Jazz by double-digits. Of course he did.

The nerves that hadn’t hit me earlier that day eventually came before my first shift a month later (I got the job). On my way to the newsroom, I read a story about how Kobe had once come to the defense of a teammate who was benched by their coach after taking an ill-advised shot.

“I think he was testing the limits of his game,” Kobe said.

“That’s what I’m going to do,” I thought during my commute. “I’m going to test my capabilities as a journalist.”

Kobe was famously dismissive about the prospect of failure. He had lofty goals and if he was ever going to achieve them, stumbling would be part of the process. Even if he didn’t reach them, failure was the only way to be sure he couldn’t. With that in mind, I tweeted the article. I would remember the date and have that post to come back to if I ever lost sight of my mission. Then I went to work in search of my limits.

I found them just over a year later, when a news director told me I was being let go. A particular show I worked on was having issues and in an effort to correct them, I would be replaced. I was upset. I drove home and opened my laptop to discover a post on a sports-related account that I followed. It was the anniversary of one of Kobe’s first playoff games, during which he had shot four air balls. Each could have been the first of the game-winners he would routinely make in the future.

I shared a link to the highlights on my own social media and began my search for new employment.

“This is my air ball,” I said aloud. “I have great things ahead of me. And when I achieve them, I’ll have this post to come back to and reflect on this moment.”

Six months later I had relocated to Southern California. I was working at a news network that I wasn’t particularly proud to be a part of, the sort of place that prompts people to respond with their job title instead of their employer when asked what they do by an industry peer.

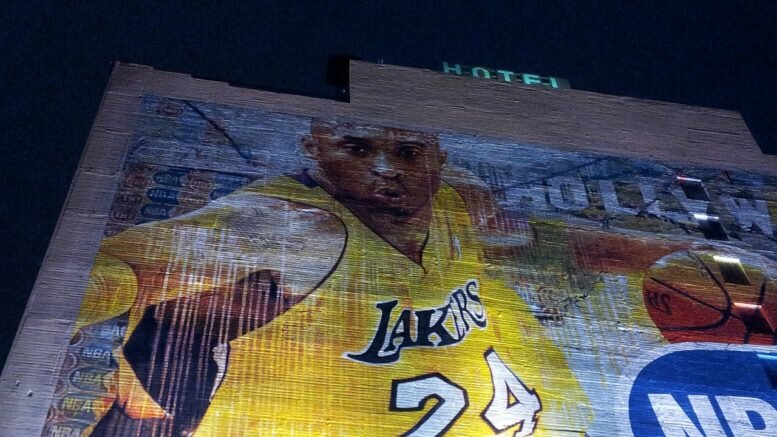

After one of my first shifts, I watched the Lakers retire Kobe’s jersey numbers.

During his speech, he imparted some timely wisdom:

“Those times when you get up early and you work hard, those times when you stay up late […] those times when you don’t feel like working, you’re too tired and you don’t want to push yourself but you do it anyway–that is actually the dream […] It’s not the destination, it’s the journey.”

I internalized his words immediately.

“I’m not where I want to be, but this is part of my journey,” I thought. “I’ll push through.”

I was excited to hear Kobe’s speech next year at his Hall of Fame induction. Maybe I’d have another milestone experience to tether to his words, a more positive one this time.

I am incredibly sad to know this cannot be the case.

Upon reflection

After receiving confirmation that Kobe had in fact passed, I began watching highlights from his games against my Kings. This lasted just a couple minutes before I lost my composure. I left my room, hugged my roommate- (the first person I could find) and I let out many tears. I came back to my room to call my parents-who still live in Sacramento-and I let out many more. I cried for nearly 40 minutes.

“Do you remember?” I asked several times before recalling my memories of Kobe’s life and career.

“Yes, I do,” my mother responded.

It was the third time I can recall crying over sports.

In efforts to redirect my emotions, my mother asked me to reflect on why Kobe’s death may have had such a profound effect on me.

Upon reflection I realized I may have more tears and strong feelings associated with Kobe than many other things in my life. But why? Until I was a teenager I hated the man. Even when I became more fond, I rooted for him to fail.

Kobe was different from several other basketball stars I followed in my youth. The NBA, like most of America, celebrates the “rags-to-riches” narrative. Humble beginnings are triumphed when players are drafted or sign their first generationally lucrative contracts. Kobe didn’t pursue basketball history with economic class ascension in mind. He did so because he thought he was meant to. It was a personal passion to which he applied his personal values.

My upbringing was more like Kobe’s than, say, Allen Iverson’s: A lifestyle most might call “privileged,” and the freedom to worry only about myself and my interests. Having lived nine years before my only sibling was born, I will always have the internal makeup of an only child. By the time my sister arrived, I had learned to advocate for myself and had developed mechanisms (some healthy, some not so much) to cope when I felt alone, let down or misunderstood. My psychological sense of life and the world began and ended with my own perspective, even in cases where I considered others. I was often (and sometimes still am) myopic and uncompromising to nuclear faults when pursuing my passions.

My attitude when I disregarded advice from friends and elders on personal matters, or vocalized my journalistic concerns and disagreements in contentious newsrooms was not dissimilar from Kobe’s.

“I know what I want, I know what’s right and I know how I will achieve these things. Furthermore, I have more faith in myself than I do anyone else; even those who may be here to help me, love me or believe they know better than me.”

Perhaps some unconscious part of my soul has long viewed Kobe as a kindred spirit. Maybe that’s why despite my innocent disdain for him, I had a poster of Kobe on a wall in my childhood bedroom, right next to some of his Sacramento rivals.

In his passing, Kobe has defied the odds in one more way; he’s made me a part of Laker nation. Living in Southern California and grieving with his most faithful followers, I hope to make my relatively new home a place of prosperity, a place where I do great and memorable things, as Kobe did after finding more productive applications for the qualities that emboldened him.